MICHAEL TOMS: John, your recent book is entitled Anam Cara. What does that mean?

JOHN O'DONOHUE: Anam cara is a Gaelic phrase. Anam is the Irish word for "soul," and cara is the word for "friend." So it means "soul friendship." It's one of the most poignant and tender aspects of the Celtic tradition that-despite their profound imagination, their great battle prowess and their great passion-there is at the heart of Celtic wisdom such a beautiful notion of friendship.

A way of explaining it is that between two people such a friendship awakened. It wasn't manufactured or produced or programmed, but it awakened between them in their meeting. It was almost as if an ancient affinity that was latent in their spirit comes awake and comes alive, and that each is joined in an ancient way with a friend of their soul.

John Cassian said that the anam cara relationship couldn't be broken by time or space or anything else. It's important to stress that it wasn't just an ideal or a metaphor for what human relationship should be, but it was an actual social construct of the time. I mean, people did have these anam cara relationships. In the book I've tried to use that image as a lens to look at different aspects of modern consciousness and the incredible spiritual hunger that haunts so many people.

MT: We might encounter someone that we feel we've met before, or someone with whom we immediately feel a rapport. Sometimes we feel that somewhere long ago, we decided to get together now, and here we are.

JO: Exactly. People say that friends are made. I don't think friends are made at all, but rather discovered. If you look back along your life, you will see that at the crucial thresholds, different people were sent to you to help you acknowledge what was going on, to recognize your own responsibility, and to bring you over thresholds. The most creative growth points in our inner journey are all due to the assistance, graciousness and surprise that friendship brings. Friendship has a secret logic and a secret destiny. Something that's startling about one's friends is that the first meeting was so contingent and so seemingly accidental; and yet, if you look back now, your life would be unimaginable without the friends who have helped to shape you and give birth to your soul.

MT: When one thinks about it, it's having friends and being in friendship that is one of the secrets of life, isn't it?

JO: Absolutely. And it was said beautifully by Aristotle in the De Anima, where he devotes several chapters to the concept of friendship. He said, "If one could have all the good things in life but be without friends, one would choose not to have the good things rather than be friendless." Because there's something radically creative in the human spirit and mind, and because that creativity is linked to the contours of absence within us, there are places of incompletion, places where we are hungry within us. And only in the kinship of friendship do we actually become one with ourself.

To put it more pictorially still, it's utterly fascinating to me that no human person ever sees their own face. We look in mirrors and we have images, but we never see our own faces. And we never see our own bodies fully either. A friend is a true mirror in which we begin to get some little glimpse of who we are and the immensity that we carry-and that sometimes haunts us. Friendship is the shelter; and it's not a complacent shelter but a shelter that settles some primal restlessness down within us. It liberates us to get into the dance of our own life.

MT: I think of the Buddhist idea of the other-that looking into the other is looking into yourself, because the other is the mirror of you. That's what I hear you saying.

JO: Yes, that's exactly what I've been saying and intending. Some of the unexpected aspects of our destiny don't actually arise within us at all but are brought along the pathway to the door of our heart by our friends.

Some friendships have brief physical exposure but a long, lingering inner presence that you never lose them in. You hear people say, "My relationship broke up," or "I lost this friend." People do break up and move away from each other, but there is some little corner of the heart, if we've loved a person, that somehow always remains open to them and attached to them in some way. The human heart is an altar of different icons of friends-starting with family and siblings-that we have made. Maybe one of our sacred duties on the Earth is to bring that altar of icons with us through time into the invisible world.

MT: John, what was it like to grow up in the Burren? It is quite an extraordinary place. There is an Irish sensitivity to the land and the Celtic relationship to nature. As a young person, what do you remember of that? Clearly it had a deep effect on you.

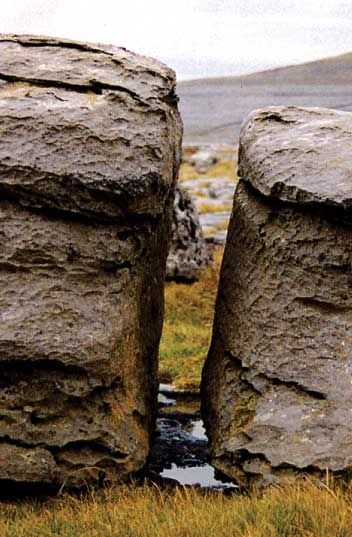

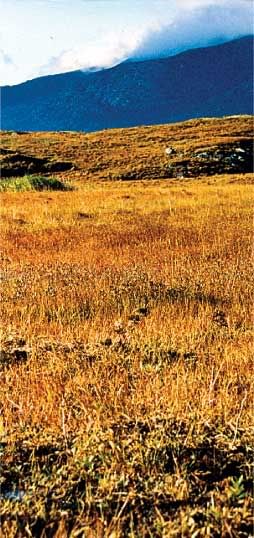

JO: It has had, and still has. It's very interesting to look at the work of psychologists like Piaget and Freud, who acknowledge that one's earliest experiences lay down the clay within the psyche. That's usually determined in relationship to parents, siblings and all that. But when you live in a wild, luminous landscape like the Burren, that landscape itself becomes an inner companion. I can remember very clearly my first moments, as a child, of recognition of the mystical wildness of this place, the strangeness of it. When the light was there the stone was white, and you could almost understand that it had been all under the sea at one stage. Then, when a shower came, the whole landscape blackened completely.

I remember going out as a little child, when my father brought me herding with him. I was too small, and I was afraid to cross over the scailps-where there is a division between the stones. He was encouraging me like this: "If you always watch where you're going, you'll never go down between them." It was lovely to walk on the solidity of that stone.

Even still, when I go home and if my head is netted or entangled, I go out into that landscape and stuff drops off me. I feel so free and so clear, because there's a grace and clarity in it, and there's also an incredible imagination in it, because no two stones in it are the same. It's a bare limestone region, so each stone has its own particular presence and shape and incredible luminosity. It's such a kind place to the spirit.

While we are talking of landscape, I wrote a poem several years ago about the death of my uncle, and the landscape of the Burren is very much in the poem because it was his identity. This poem is called "November Questions." November is the month of the dead in the Christian tradition, but in the Celtic tradition it was Mi na Samhna, the month of when the two regions, the mortal world and the eternal world, flowed into each other; the veil between the visible and the invisible was pulled back. So I called this poem "November Questions."

It's in the form of a series of questions addressed to the uncle who has just died, because the loneliest thing about losing someone to death is that you wonder where they are, who they're with, and what's happening to them. At the end of the poem, then, there is a subversion of that whole line of questioning, and it turns the attention another way.

Here's how it reads:

Where did you go

when your eyes closed

and you were cloaked

in the ancient cold?

How did we seem,

huddled around

the hospital bed?

Did we loom as

figures do in dream?

As your skin drained,

became vellum,

a splinter of whitethorn

from your battle with the bush

in the Seangharraí

stood out in your thumb.

Did your new feet

take you beyond,

to fields of Elysia,

or did you come back

along Caherbeanna mountain

where every rock

knows your step?

Did you have to go

to a place unknown?

Were there friendly faces

to welcome you, help you settle in?

Did you recognize anyone?

Did it take long

to lose

the web of scent,

the honey smell of old hay,

the whiff of wild mint

and the wet odour of the earth

you turned every spring?

Did sounds become

unlinked,

the bellow of cows

let into fresh winterage,

the purr of a stray breeze

over the Coillín,

the ring of the galvanized bucket

that fed the hens,

the clink of limestone

loose over a scailp

in the Ciorcán?

Did you miss

the delight of your gaze

at the end of a day's work

over a black garden,

a new wall

or a field cleared of rock?

Have you someone there

that you can talk to,

someone who is drawn

to the life you carry?

With your new eyes

can you see from within?

Is it we who seem

outside?

(c) 1994, John O'Donohue

MT: The Celts have an interesting notion about death. They seem to see it as a birth, as part of life, which brings up the idea of what happens at death. Having been raised in an Irish Catholic family, I remember the Irish wake. The death of one of my aunts when I was ten years old was one of my first encounters with death. I remember the wailing that was going on in the room with the open casket and the body, and in the other room there was laughing and joking and telling stories and passing around the beer. It was an interesting juxtaposition. That comes from the Celtic tradition, doesn't it?

JO: I think it does, because the Celtic notion of the afterlife was a place where there was great celebration, plenty to eat and plenty to drink. And it didn't seem at all tarnished or damaged by a negative view of the afterlife. I suppose it also explains the warrior code and their traditions of honor, and how it was more important to endure death rather than dishonor-there wasn't a massive severance going into the invisible world and death. The Irish have a real ability to celebrate death. And one of the lovely things is the wake, as you were saying there now.

The wake is an important reverence, because in the wake it is recognized that the newly dead person shouldn't be left on their own with their new journey. It's a new experience for the body that has carried this life for sixty, seventy, eighty years. But it's also a new experience for the spirit of the person, who is now bodiless and has gone into the air element.

There's a lovely story from the Cork area about the soul that kissed the body. The body had died and the soul was on its way out the door. Just before it went it turned and looked at the body, and it felt such a sense of poignance for the body in which it had lived for seventy years that it went back and thanked the body and kissed it three times before it went on its way.

So the Irish recognize the dual loneliness and the dual novelty there and try, by gathering round that new experience for both body and soul, to shelter it and bless it. It's a great opportunity, and was even more so years ago when they had the keening tradition-the tradition of the wailing for the person who was gone.

I remember just meeting the last bit of that in Connemara, and the wailing of these people who keened the departed one was like no crying I've ever heard. It would go to the bone in you. Any bit of personal sorrow in your own life-even if you weren't related to the dead person-was totally, absolutely released by that. It cut into you. But it also gave the bereaved a chance to absolutely loosen the wells of grief within themselves.

The other part of the wake, then, of course, was the celebration of people telling stories about what the person did when they were young, what has happened-things long forgotten. So in a way the wake was a gathering of the fragments of the memory of the departed one, almost as a shelter to now help her or him on their new journey. It was a very important ritual. Even still, at home, when anyone dies, everyone in the village and surrounding villages always goes to the funeral. I heard of somebody from Germany who was over visiting someone there a few years ago, and three neighbors died in the week. The German went away thinking that the Irish did nothing else but go to funerals.

MT: The invisible world holds great importance to the Celts. Could you talk a little about that?

JO: One of the lonely things in contemporary culture is that that which is not visible is not real. We've equated reality with visibility and with images. For the Celtic consciousness and the Celtic mind, the invisible was just as important as-if not more important than-the actual visible. And for instance in the Thain, which is the nearest the Irish tradition comes to an epic, you have people who materialize, come out of nowhere and are suddenly physically there, and then go into nothingness again.

It reminds me of a story my father used to tell at home of a man who was friends with a priest. And he said to the priest, "Where do the spirits of the dead go when they die?" And the priest wasn't willing to answer him, but the man kept at him anyway. And the priest said, "What I'm about to show you now you will never tell anyone." Needless to say, the man didn't keep his word, but the priest, it was said, raised his right arm, and the man looked out under his arm. And it was said that he saw the spirits of the dead as thick as the dew on the blades of grass, everywhere around.

That's the Celtic tradition, that the dead are not far away, but stay near us. And it coheres very beautifully with the wonderful answer that Meister Eckhart gives to the same question, "Where does the spirit of a person go when the person dies?" And he said, "No place. Where would you be going to?" So that means that the dead are actually all around us and are present with us. Now I'm not talking about spiritualism and all this stuff about mediums, but I think the next big step in our evolution as a species will be that that veil will be drawn further back, and that we will sense the spirits that are here with us.

When I'm praying for somebody who is grieving, I pray that the sore of absence will become the well of presence-that when you stop mourning the person and their physical loss from your life, then very often what you regain is a sense of their invisible presence with you. I think we should pray to the dead as well as praying for them, because they are probably in a rhythm and in a wisdom that they can give us incredible guidance.

Many times in my own life I've been in really hard places and on very sore thresholds, and when I've asked for blessings from my father and my uncle-the Lord have mercy on them-they've always come. The dead probably inhabit a different time rhythm where they can see our future as well as our past. Very often in our journey there are huge boulders of misery poised over our path, and our friends among the dead hold them back until we can pass underneath.

The corollary of that is, of course, that the dead now know more about me than they did when they were living, so it could make for very interesting psychological situations. But I also think that their new knowledge of us is absolutely equal to their new understanding and their new forgiveness, so that they carry no remorse, no regret, and no anger towards the living, but a profound sense of pathos. I'd say it's one of the things that will amaze us when we ourselves come into the eternal world, which is here in the middle of this visible world, and when we will be near to behold those that we love still living. I think the sense of pathos and feeling for them will be overwhelming.

This article has been excerpted from New Dimensions

Program #2666.

No comments:

Post a Comment