Backstage Pass: A conversation with Love's Arthur Lee, Part I

Steve Rosen

STAY TUNED: Part II will appear in the May 9, 2008, edition of Goldmine.

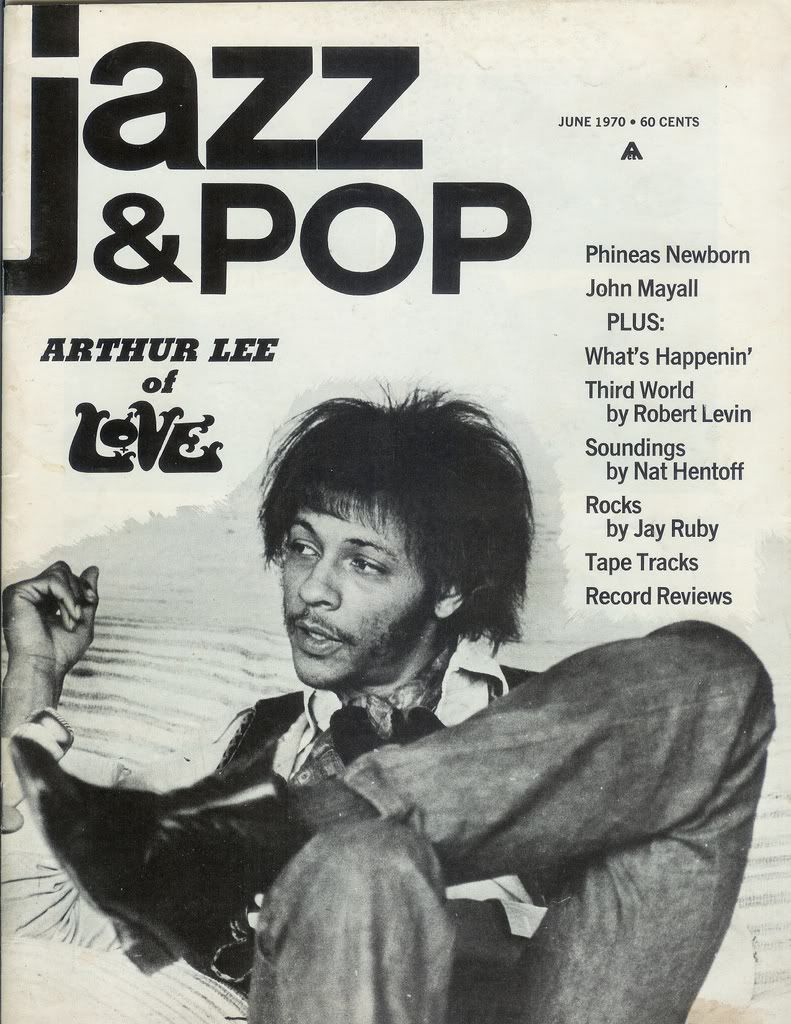

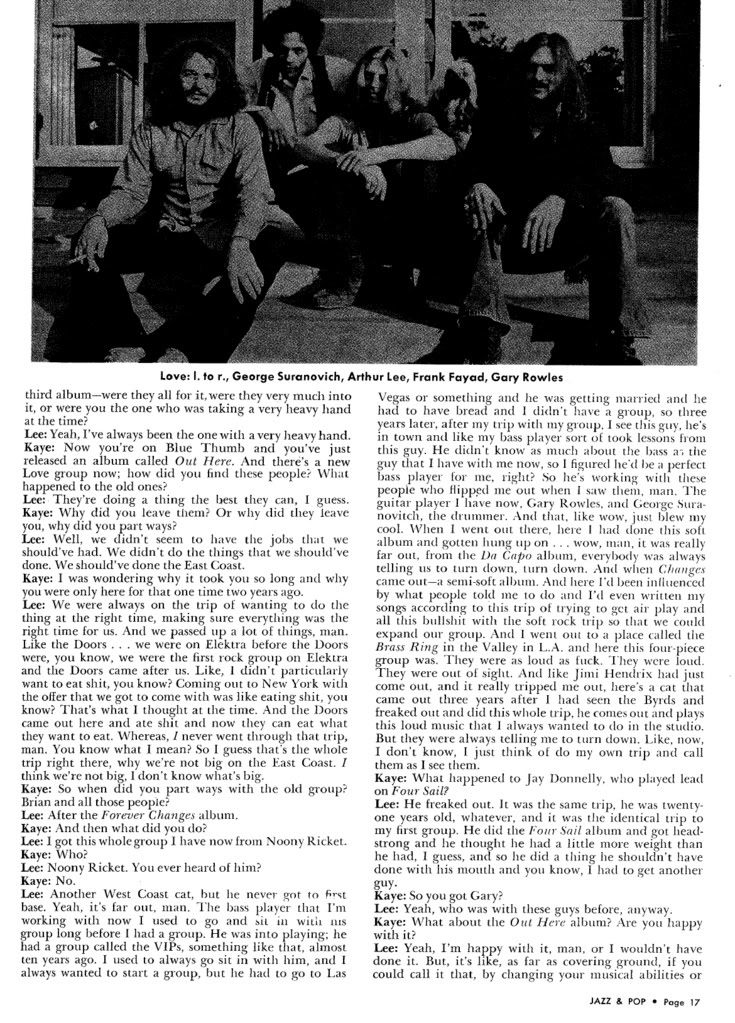

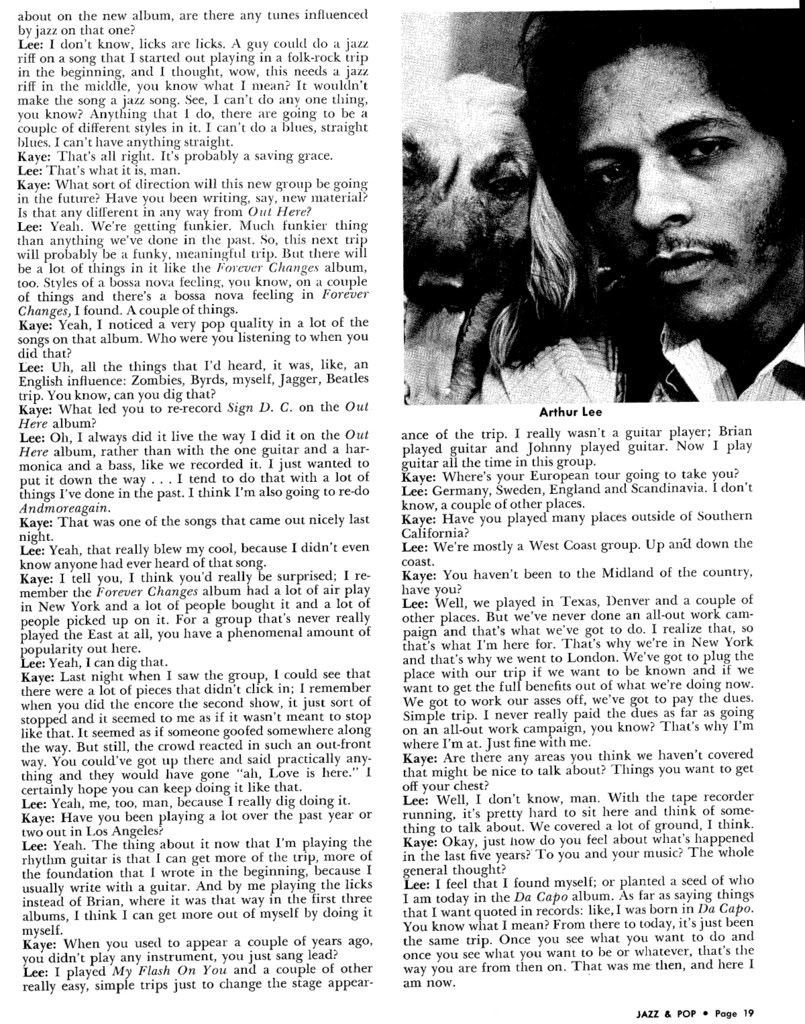

Arthur Lee, gangster of love, came bopping through the conference room doors of RSO Records. His head was shaved and his clothes were mildly unkempt. A moustache adorned his upper lip, facial hair suggesting something between a felon and a pimp.

Verbally, his thoughts came out in staccato bursts. He is part hustler, part hipster. The eyes were narrowed and a faux smile, a sneer, played upon his face. It was the beginning of 1975, and the Memphis-born musician was back with Real To Reel, the first Love album in four years and what would be the final Love album for nearly two decades.

As he lowered his thin, but muscled, frame into a chair, his gaze took in the room around him. Arthur was not high, but he acted like it. His head darted back and forth, and he tended to mumble beneath his breath. Lee’s body coiled and uncoiled as if preparing itself to strike. Apropos of nothing, he addresses the tape player on the table before him: “I don’t like violence, but I love to fight.”

For the next hour and a half, he did wage a sort of personal battle. As he called up all the old demons — former bandmates, publishing companies, managers and record labels — he tried in vain to exorcise them. By turns, Lee revealed anger, disillusion and a type of hard-earned pride.

By the time of this interview, Arthur Porter Taylor (his birth name) had been bounced around from label to label and had lost virtually all of his music publishing to conniving manipulators. Maybe there was good reason for the anger.

Finally seated, he emits a mad cackle, the first of many. It is startling in its intensity and will serve as a warning sign for areas he won’t talk about. When Arthur laughs, there is nothing funny about it. The room is hushed, save for the strains of his new album playing from monitors. He nods in time to the music.

“It’s an R&B-type thing and pretty funky. I’ve got to see if people are going to dig my trip.”

The stage set, Arthur Lee attempts to unravel himself.

Would you mind going back and talking about how you first got into music and the Los Angeles scene?

Arthur Lee: No, I don’t mind going back at all, man. My aunt used to take me around the beer gardens, man, when I was about 4 or 5 years old. That ain’t how I got into it, but that’s one of the things that had to do with it. F**k, man, I dug music from as far back as “The Hucklebuck” (this was an instrumental song from 1949 that made it to #1 in the R&B charts). Man, doing the “Hucklebuck!” “The Hucklebuck,” “The Sh-Boom,” you know? It just rang bells in my head. I said, “Wow, man, I think I can do that!” But I didn’t know how to go about it.

You know, if you’ve got a talent, it’s one thing, but you’ve got to know the person to put you on the stage to perform your talent. And that’s been my problem ever since I’ve started. What, am I gonna go and tell some other dude that I can sing better or good as what I hear on the radio? You know what I mean? It’s just listening to the f**kin’ radio, man — listening to all kinds of music, all kinds of music.

What was your first band?

AL: My first band started at Dorsey High School. I had a school basketball record while I was there. Arthur Lee! I like sports, man. I like livin’, ya know, good trip.

My first band was [with] Johnny Echols, that’s that cat who’s on that Forever Changes album. We went to school together, and he had a band. I was playing congos or congas, or whatever you call them, at the time and a little accordion, a little piano. Billy Preston went to Dorsey, too. Probably a lot of cats and musicians that went to Dorsey, man. Pete Townshend… Ed Townson… What’s that cat’s name? Check this out. I don’t give a f**k what he says; I mean, this interview could go ’round the world, man. But the truth is the truth. This dude used to be a janitor and also an athletic groupie. And now, he’s with The Fifth Dimension. You know the heavy-set guy in the Fifth Dimension? What’s his name? Ron Townson (this is the correct name)? Pete Townshend? Eric Townshend? Yeah, me, him and Billy, man! We all went to Dorsey. Well, he didn’t go to Dorsey, he was the janitor there. I was stealing lunches, and he was sweeping the floor. It cracked me up!

Did you ever play with Billy?

AL: Billy? No, man. Billy always seemed like… well, we were two different types of people. He’s got his thing, and I’ve got my thing, and I’m glad of that. It’s a negative and positive world, so that makes sense.

When did the LAGs happen?

AL: Oh, that. I guess that was the first recording band. Or was it the American Four? I think it was. No, no, no, yeah, it was not the LAGs, it was the L-A-Gs. I was into Booker T and the MG’s, ya dig it? The M-G meant Memphis Group. L-A-G would mean the L. A. Group. It wasn’t LAG — I wasn’t laggin’!

I was lagging when I was high school and the bathroom a lot. We were pitching pennies, but actually we were pinching pennies, but they were really dollars. I was averaging like 18, 20 bucks a week, man. I wasn’t doing bad, man. The teacher comes in one day and this f**kin’ bathroom is all filled with smoke.

This cat comes in there, and he says, “All right, I knew you guys were in here gamblin’ and smoking! And I want each and every one of you to go and report to the boy’s vice principal right now. I’ll be over there in a few minutes.” Wow, man! Can you imagine that shit? That’s like some cat tellin’ me, man, “Hey, look, you go out and sit in the electric chair, and I’ll be up there in a minute to turn the juice on.”

Did The LAGs ever record anything?

AL: Yeah, we did a song called “The Ninth Wave” on Capitol Records, man. It’s f**ked, man. I heard, like, you go to a big record company or something, if they sign you, they rip you off. So, what I did was give the people not the best thing that I had — to test them. And if they pushed back, then I’d give them the best thing I had.You give them the best, and you make sure that you’re the best, or f**k, you’re outta there. You know? And I was outta there! (laughs). It must have been ’63, ’64.

How did they find you?

AL: How did they find me? Now there’s a good question. I kept telling these guys, Adam Ross and Jack Levy... they used to be managers (also producers) of a group called The Rivingtons.

“Papa-Oom-Mow-Mow.” I figured I couldn’t go wrong.

I went to a lot of people, man. I went to a lot of black people first, because that was the neighborhood. I’m from a black neighborhood, and I went to J.W. Alexander of Sire Records, who was Sam Cooke’s manager. He turned me down. I went to Billy Revis of Revis Records — that’s how I met Jimi Hendrix (the guitarist recorded his first solo on Rosa Lee Brooks’ “Utee” single in 1964). And there was nothing happening there.

So, f**k it, man. I was working out in Montebello under the name of The American Four. Give ‘em their own name, man: America (laughs)! Then, maybe you can make $20! There’s gotta be a gimmick. You can’t be good. Whoever heard of a good musician? But Love ain’t no gimmick. So, that’s when all that shit ceased. Yeah, changin’ the name to Love, man, really tripped my life out.

Where did the name come from?

AL: The name came from… Lou Adler (produced Mamas & The Papas and other acts) ripping me off when I was called The Grass Roots. I think it was Lou Adler; I don’t know.

But, I think he had done the records and some shit, and The Grass Roots were on that label (Dunhill Records). All of a sudden, that Barry somebody (Steve Barri) was playing at The Trip (club on the Sunset Strip). And we’re in, like, the biggest f**king group in Hollywood! I know it, man, just word-of-mouth group.

We didn’t have a record out, and we’re called The Grass Roots. The next thing I know, I look up on the marquee and there’s (Steve Barri) and The Grass Roots. Those cats were from San Francisco who aren’t even the guys in The Grass Roots now. But who gives a f**k, man?

Where I got the name Grass Roots from was from Malcolm X. Because Malcolm X said in the days when brothers was slaves, as if they aren’t now, there were two kinds of so-called niggers. One was a house nigger and one was a field nigger. The house nigger wore the same clothes his master wore. If the master got sick, he’d say, “Well, what’s the matter? Are we sick?” (laughs). Then, there was a field nigger. Like if the house caught on fire, the field nigger would pray for a breeze, man (laughs).The people that were doing something for themselves definitely could not be doing something for somebody else to get recognized. Nobody gives you freedom. You go out, and you get your own freedom, if you think that’s where it’s at. So, that’s where I got the name The Grass Roots. I thought he was on it. Right on (laughs)?

When did the wig thing come in?

AL: When I saw Mick Jagger on TV. It was the Red Skelton Show, the first time The Rolling Stones ever played.

What was it about Mick Jagger that so moved you?

AL: No, it wasn’t Jagger, actually; it was a cross between Jagger and Jimi Hendrix. I started working on it when I was at my girlfriend’s house one day. All of a sudden, man, I turned around, and there’s this car accident and his leg is all f**ked up, and these guys are driving by, and they jump out of their car. And the guys that jumped out of the car were The Valentinos. Bobby Womack, the Valentinos? And they had hair as long as you in 1963.

I looked at it, and I looked at their head and their hair and everything. “Something must be happening here! I don’t know what it is.” And the next thing I know, I saw Jimi Hendrix going in The California Club over on Western and Santa Barbara. It was called California Club then. Well, he was walking in, and he had a hoodoo priest suit on, man, and some shoes with runned-over heels. And I was walking right behind that dude, and his hair was real long. You know, “Whoa! There must be something in this trip!

So, I put a wig on, man, right there in Montebello, and start singing Beatle (sic) and Rolling Stone (sic) and “oop oop a doo” and all that shit, funky, and the next thing I know, man, I go to Ciro’s, and The Byrds are playing there. And I bumped into Brian Jones of The Rolling Stones, and he looked at me... he couldn’t believe, I don’t think. I looked at him, and I know I wasn’t believin’. Then, the next time, I saw Jim McGuinn and The Byrds and those guys.

Like, the music in my head that I had in the back of my head (whistles a high to low note) — way in the back — I knew I could do the things that I saw The Byrds doing at Ciro’s. Packin’ the house every night, all these people jumping up, and freaks flying around and carrying on. So, man, you know, I jumped on the wagon, because when they left, they left a huge following of people here. So, I didn’t get my trip from The Byrds, but they was a big influence on the first Love album. You know what I mean? But see, I was hungry, man.

I said, “I’ll go around, and I’m gonna do this thing until I’m capable of doing my thing.” That came about just about right after Da Capo, I think. It was sorta like Da Capo and Forever Changes, and then, I started doing my style of things. Which is, what do they call people, ventriloquists or some shit like that? I think I can do that with my voice as far as singing goes. I can sound like a lot of people, man. So, that’s my thing. I’m not trying to tell nobody I’m the best; I just want them to know I am (laughs). You dig it?

What about your relationship with Bryan MacLean?

AL: You mean the last time I saw him? I got two gates, man. To get to my pad, you’ve gotta go through two gates — bottom of the hill and then you get to the top of the hill, you go to another gate, right? This dude jumps over the gate, goes past my guard dogs — so-called guard dogs — jumps in the motherf**kin’ window, man, and wakes me up.

My bodyguard or whoever is sleeping on the couch, I said, “Who let you in, man?” He says, “Nobody, I came through the bathroom window.” “Who the f**k are you? Joe Cocker? You know, I haven’t see you in 10 years, man (laughs)! What the f**k… Well, look, that’s cool, but just don’t do it again.” Next thing I know, whammo, he’s jumping the fence again. So, the last time I saw Bryan I slapped him. Not hard. I missed. As a matter of fact, I f**ked up my hand, but I guess it was meant to be, because where is violence anyway? That’s nowhere unless you want to off somebody (laughs).

He made some good music with you, though.

AL: He did. He was a great musician, great writer. It’s too bad he doesn’t know it. That’s the only thing that’s wrong, man. Like I was telling you — I don’t know if I was telling you or the guy that was interviewing me a little while ago — you gotta know the person to put you onstage and do your thing. You’ve gotta know somebody to get to where you wanna be.

How did you get together with Jimi?

AL: He played on a record called “My Diary.” This chick’s mother found her diary, and I was f**king the shit out of this chick for a year. S

he wanted this chick to be with a lighter-skinned black dude with the straighter hair. And she found her diary, “And we f**ked in the alley and f**ked in the streets/Then we got somethin’ to eat.” But it really broke me up when she found out about the diary bit. (Sings) “Why did my mother find my diary!” And Jimi’s (sings guitar lick), “Doo-doo-doo, doo-dedoo-doo…”

Yeah! Yeah, man, that’s how I met Jimi Hendrix.

And then the next thing I know, I’m playing at the Fillmore West. There was this cat called Pigpen in the Grateful Dead, and, like, everything is peace, love, and acid tests and all that shit. So, I go there, man, and I’m peace, love, you know, and we’re playing and we’re getting standing ovations. And the second billing is a group called Grateful Dead. I’m in the bathroom, and I’m combing my curlies, straightened hair, making sure that my triangle glasses are on straight and my pants are crooked and the zipper’s open (laughs).

And this cat Pigpen from the Grateful Dead came in and said, “Hey, you know something, man? I heard that people that wear triangle glasses usually have triangle heads!” And I said, “Hey, right on, man! Peace, love!” Then, I went into the other room, and I thought about it (laughs). He’s dead now. That’s a trip, man. I had nothing to do with it, but anyway he was a trip. You get so hung up, and that’s what you get for getting hung up and going down one street too fast. Because there’s always something coming on the other side. You know what I mean? I ain’t got no racial problem, man, at all. I’m just prejudice (laughs).

How did you decide that you wanted Jimi to play on the record?

AL: This guy at Revis Records, Billy Revis, told me that. See, what I needed was a guy that played something like, (singing) “It was a gypsy woman around the campfire/Wheeoo!”

And that type of guitar. Well, he said he knew a dude that could do that backwards, man, and he wasn’t lying because he brought Jimi in. It’s out of sight, man; he’s out of sight now.

Was Jimi playing with anyone then?

AL: He was playing with Little Richard. He was playing with the Isley Brothers. I think he was playing more with Little Richard than the Isley Brothers.

Did you ever talk about starting a band together?

AL: Yeah, we were gonna start a band. He wanted to use Stevie Winwood, and there’s a dude, his name is Remy Kabocka.

He played with Ginger Baker’s Air Force. He’s got his own band now. I just got back from London and he was over there. What was the question?

How you were going to start a band with Jimi.

AL: It was gonna be called BandAid. You know what I mean? That was Jimi’s idea but he died, so f**k it. The name was still cool (laughs)!

Part II of the Arthur Lee interview will appear in the May 9 edition of Goldmine.